Into the Archives!

A donation turned preservation project…

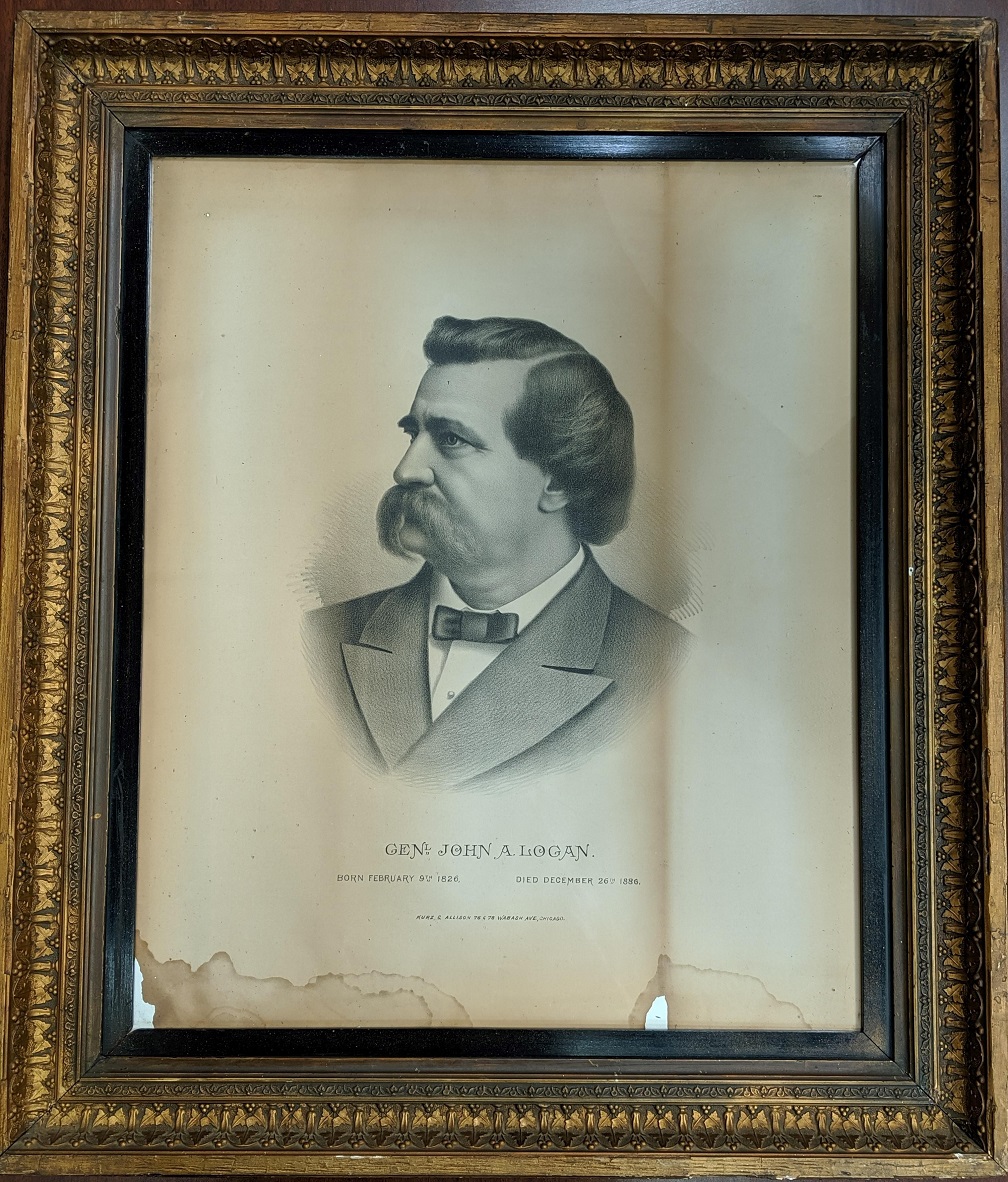

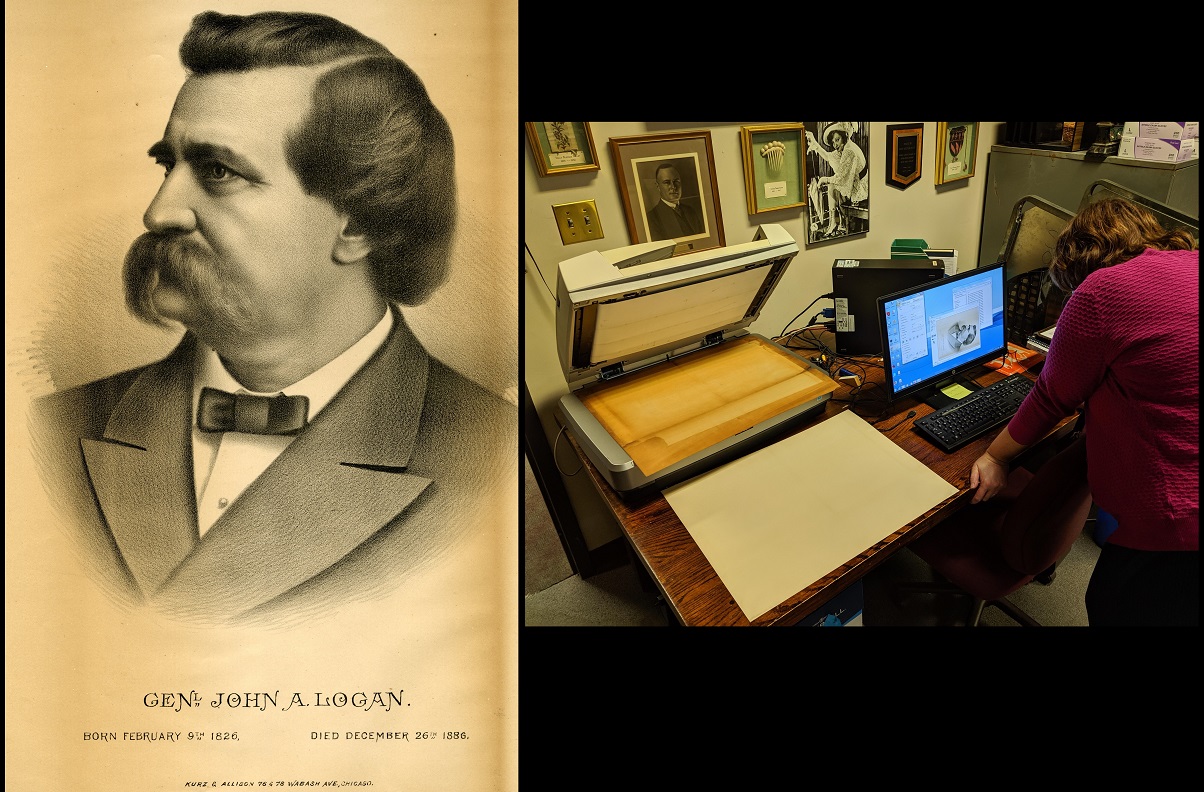

Born February 9th 1826, Died December 26, 1886

Kurz & Allison 76&78 Wabash Ave., Chicago

Donated by Kathryn Smith

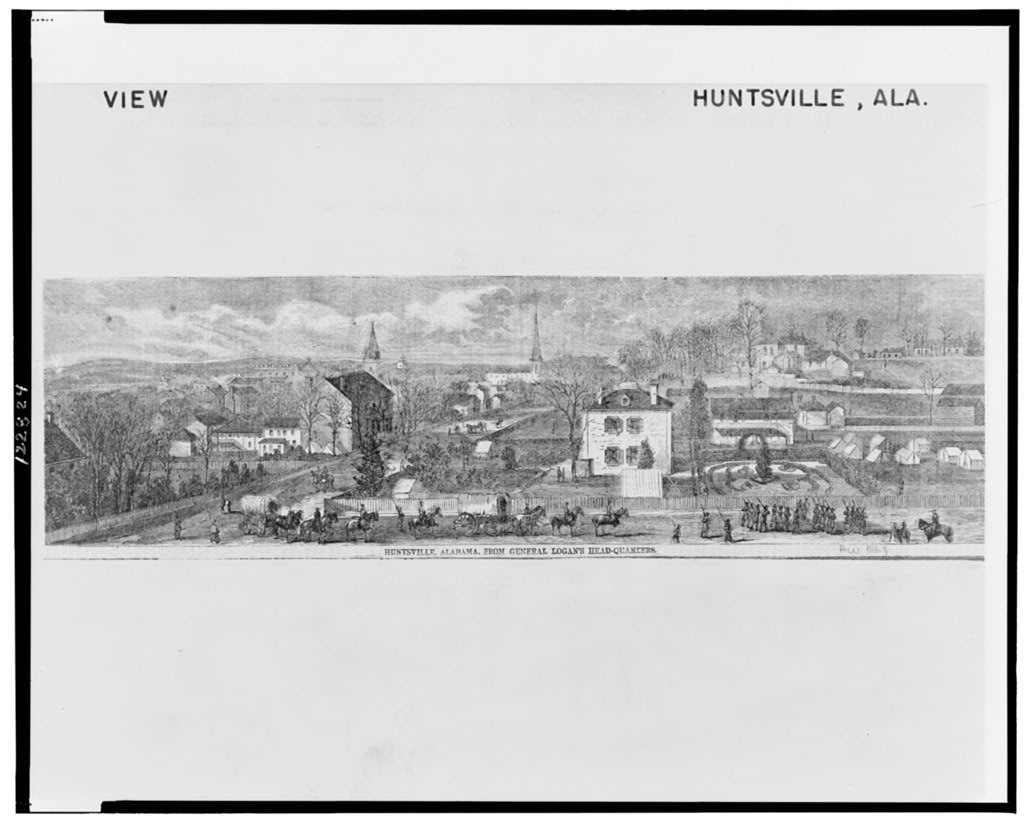

Early in July, a portrait of Civil War general John A. Logan (1826-1886) was donated to Special Collections. Logan, an Illinois statesman and soldier, was a Union officer stationed in Huntsville during its second occupation by Union troops (1863-1865). Known as “Black Jack” Logan, he resided and headquartered in the Rhett House (603 Adams Street). General Logan had a lengthy political and military career; however, he may be best known today as the man who conceptualized Memorial Day.

https://www.loc.gov/item/99404219/.

All images were captured from the Huntsville History Collection: http://huntsvillehistorycollection.org/hh/index.php?title=Place:603_Adams_Street_SE.

Left: C.1863 photo with Federal troops in foreground, Harvie Jones Architectural Collection

Middle: Bryson Photography, Huntsville Madison County Public Library

Right: Rhett House in 2010, image by Deane Dayton

The donor mentioned that the graphite sketch by “Kurz & Allison…Chicago” is hypothesized to have been made in commemoration shortly after his death. It had been in her family for years, and for much of her lifetime had been loaned to the Rhett House occupants for display.

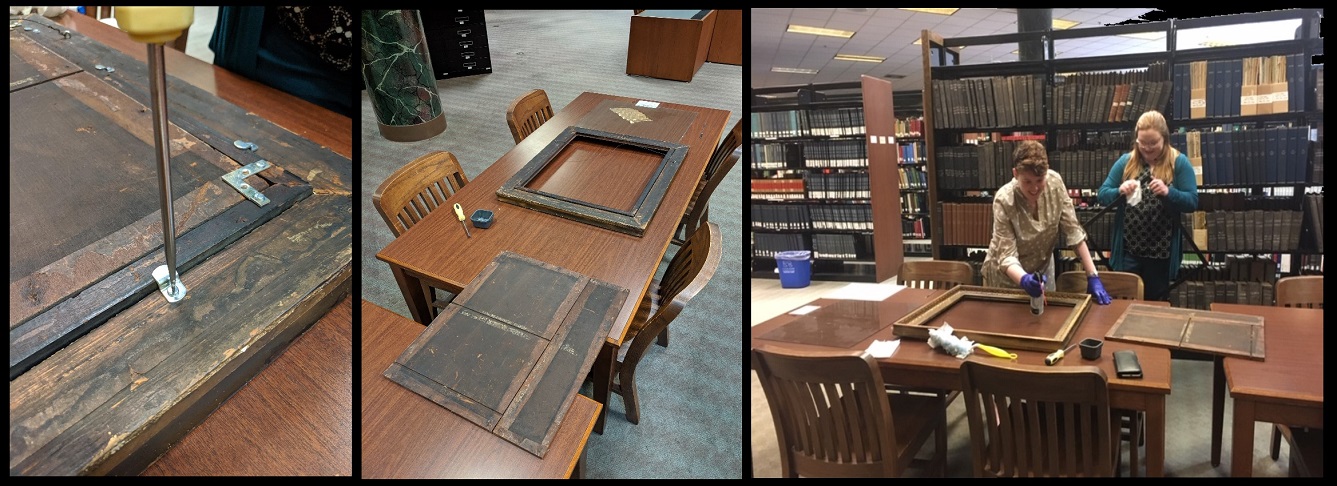

Upon receiving the portrait, Special Collections staff went about assessing the item and cleaning it. Most of the wood framing looked original, albeit covered in different layers of wood stain and paint. There are signs (old adhesive stains) that there was originally paper glued to the back of the frame, a common practice for ensuring a level of permanence and protection. The glass and particularly the hardware are more modern than the frame itself.

Middle: Deconstructed frame - the light portions of the wood backing are old adhesive stains.

Right: Special Collections staff Heather and Cait cleaned the wood and glass.

Once the hardware was unscrewed and the frame taken apart, we did a full cleaning of the frame and portrait. For the glass, we used a spray glass cleaner on the side that would NOT touch the sketch, and dry-wiped the side that WOULD touch the sketch. We used a duster and a dry cloth on the frame, and sparingly used canned air to remove dust from the crevasses around the floral carvings. For the portrait, we used a VERY soft brush to remove particles that had made their way into the frame over the years (we did not brush the portrait, but rather around it). Admittedly, we did the best we could with the limited suitable cleaning supplies we had. A few good rules to think about while taking care of your collections at home:

- FORM A PLAN. What supplies are you using? Are there parts of the frame and image that can or cannot be touched by the supplies?

- DON’T DO ANYTHING YOU CAN’T UNDO. For example: don’t write on anything with ink; don’t fold things that can’t be unfolded; don’t use harsh chemicals to clean; limit direct sun exposure when displaying anything; etc .

- DON’T USE ABRASIVE CLEANERS (both chemical and texture). For example: most cleaning supplies like glass cleaner, polish, and disinfectant wipes contain harsh chemicals that could harm or hasten the degradation of your items; and items that wipe, like disinfectant wipes or textile dusters can catch on brittle or flaking material.

- BE CAREFUL and MINDFUL with your beloved family treasures as you clean

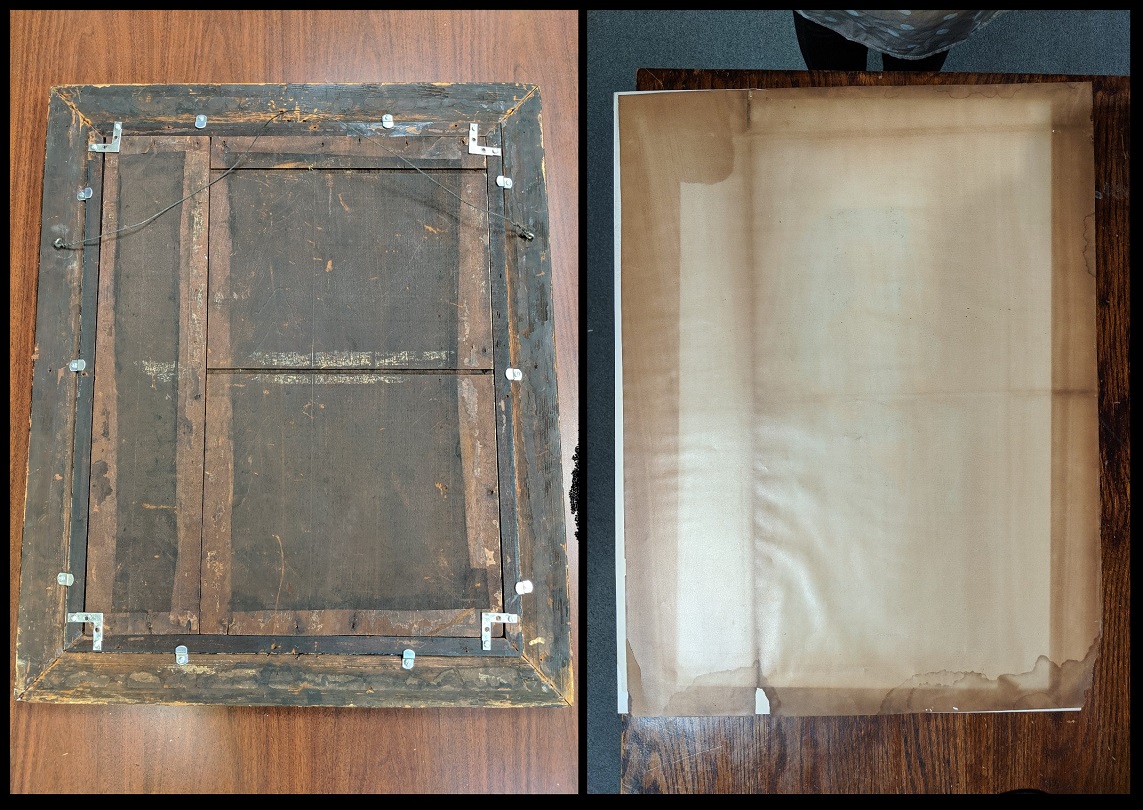

Right: One vertical and two horizontal discoloration lines are visible on the back of the portrait, matching the seams of the three wood sections.

The portrait also has discoloration from water damage, visible at the bottom.

From the front of the portrait, we could see there was a vertical stripe of discoloration. Upon deconstructing the frame, we found out why. The back of the wood frame was comprised of three sections, and layered in between the wood and portrait was a piece of heavy paper backing. The portrait having direct contact with the heavy paper, which is very acidic, is enough to discolor the portrait over time and make it brittle to the touch; however, that did not explain the specific stripe of discoloration. On the paper backing layer and on the back of the portrait, more lines were visible, in the exact pattern of the three wood sections. It is possible that if the portrait was displayed in direct sunlight for long periods of time, the exposure to UV light could have faded or bleached the portrait’s paper in every area except where the seams of the wood backing ran. To help protect the portrait, we removed the heavy paper (originally between the portrait and wood backing) and replaced it with archival-quality buffered paper, which neutralizes acidity.

Right: Archivist Shalis scans the portrait.

Before putting the frame back together, we took time to scan the portrait. By creating a digital image of the portrait, we will be able to provide copies of it to researchers and use the image in future exhibits. The framed portrait (now all back in one piece) is stored in the HMCPL Archives on the 3rd Floor of the Downtown Huntsville Library. It is now in our framed portrait collection, items of which go on rotational display in the Heritage Room gallery.

If you have questions about local history or genealogy,

Call us: 256.532.2360

Email us: hhrdept@hmcpl.org

Keep on digging!