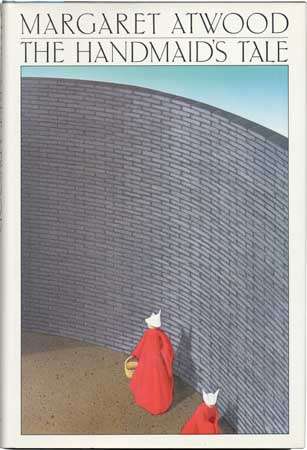

Book Review - 'The Handmaid's Tale' by Margaret Atwood

A female dystopia mutated to its logical extreme Margaret Atwood wrote ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ in 1984, a very important year in the history of dystopian fiction. Perhaps the number of the year inspired her; most definitely, the leanings toward theocratic authoritarianism expressed by organizations at that time such as the Moral Majority. The dystopian framework was the best suited for a novel about events that had happened multiple times throughout human history, projected into a possible recurrence in the U.S. Atwood has repeatedly insisted that she invented none of the developments in the novel; everything that happens in the novel has occurred at some point in the past. So here we are in 2018 and ‘The Handmaid’s Tale,’ along with ‘1984’ and several other dystopian novels have seen a not very surprising increase in sales.

A female dystopia mutated to its logical extreme Margaret Atwood wrote ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ in 1984, a very important year in the history of dystopian fiction. Perhaps the number of the year inspired her; most definitely, the leanings toward theocratic authoritarianism expressed by organizations at that time such as the Moral Majority. The dystopian framework was the best suited for a novel about events that had happened multiple times throughout human history, projected into a possible recurrence in the U.S. Atwood has repeatedly insisted that she invented none of the developments in the novel; everything that happens in the novel has occurred at some point in the past. So here we are in 2018 and ‘The Handmaid’s Tale,’ along with ‘1984’ and several other dystopian novels have seen a not very surprising increase in sales.

Two seasons of a new TV adaptation have been broadcast, with the expectation of a third, so the timing seems right to re-read this novel. ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ is a series of cassettes recorded by a handmaid from the society of Gilead, the theocracy that has superseded the government of the United States. We know that her real name was June but her handmaid name is ‘Offred’, meaning that she is a handmaid ‘of Fred’, the first name of her Commander and progenitor of an heir to whom she will, it is hoped, give birth. Offred includes flashbacks to her former life frequently, when she fell in love with a married man who divorced his wife, then married June, followed by the birth of their daughter. The elimination of women’s rights first surfaced as a law forbidding any woman to work as well as a seizure of their bank accounts, leaving the married ones with no option but to depend totally on their husbands. Her husband Luke reassures her, telling her that at least they’re together and that he will always take care of her. This is small consolation to June, who wonders if he might like this new arrangement, virtually owning her. In the new society, handmaids are the fertile women that are intended to bear the children of the Commanders. The reason for mass infertility is never explained but the patriarchal rulers of Gilead never admit the possibility that some of the men may be infertile rather than the women. The monthly Ceremony, in which the handmaid lies on a bed between the wife’s legs and spreads her own for the Commander to impregnate her, is a reenactment of the Old Testament passage in which Jacob took two handmaids, Bilhah and Zilpah, to bear him children when his wife could not and Abraham took his wife’s handmaid, Hagar. Interestingly, this society is NOT Christian but it is strongly rooted in the Old Testament. In fact, sincere Christians, including Catholic priests and bishops and Quakers that actually attempt to help people, risk and, often, lose their lives, mostly through hanging and being displayed on a huge wall along a very heavily traveled main thoroughfare. The wife of the Commander was known in the past under the name Serena Joy, a Tammy Faye Bakker-like singing and crying evangelist that Offred remembers seeing on TV many years earlier.

When the Commander fails to impregnate Offred after a few months of trying, Serena arranges, unbeknownst to the Commander, for Offred to have sex with the Commander’s driver, Nick. Offred is never absolutely certain if Nick is one of the Eyes, the secret police that ferret out violators of the rules, but she takes a chance on him as she is starved for human contact and love. Offred and Nick, therefore, begin a series of assignations, unauthorized or approved by Serena. At the same time, the Commander gives in to temptation himself by inviting Offred up to his quarters in the evenings, without his wife’s knowledge, in which he attempts an awkward kind of courtship involving games of Scrabble, even violating the rules by allowing Offred to read books while she is there. Offred, who has no rights, seizes these opportunities between the Commander, Serena, and Nick, to exert what little advantage and power she can extract from the situation, even if it means taking greater risks. The novel retains its power 30 years later. We see how a woman’s identity is chiseled away so she is left with a very small core of integral self. She takes comfort from small gifts, such as the pseudo Latin phrase scribbled on the wall of a closet, presumably from a previous handmaid from the household, translated roughly into “Don’t let the bastards get you down.” She still possesses enough self-esteem to keep struggling, to continue to persist in finding a possibility of hope and deliverance. One habit that Offred the narrator indulges in that I found a bit irritating is the tendency to dissect common words in her head to get to the root meaning, words such as “household” and “charity” and phrases such as “sitting room”. She says “these are the kinds of litanies I use, to compose myself” and I understand that it is a coping mechanism. I just wish she had used it a little more sparingly. The repetition works, in a way, because a woman in such a position has to occupy her mind with some diversionary tactics, much like the prisoner marking the number of days of his sentence on his cell wall or pacing the floor. Anyone held captive in a confined space, either physically or spiritually, will indulge in such a practice. This being a dystopian novel, one can imagine that the outcome may not be optimistic. However, there is an afterward consisting of a transcript of a symposium on Gileadean studies in 2195.

The keynote speaker refers to the series of cassette tapes, an audio document labeled ‘the handmaid’s tale’. Much like the history detectives of the current age, a search for evidence of the real ‘Offred’ and the real Commander Fred is discussed. ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ acquires a status analogous to a document such as ‘Incidents from the Life of a Slave Girl’ from our own slave-holding past. Such a parallel is very appropriate as Offred, as well as most of the women from the Gileadean era, are/were slaves to varying degrees. The conclusion puts the tale in a historic context, encouraging in the sense that such times do eventually come to an end, with the possibility for a more equitable future. I believe Atwood meant for her novel to be cautionary, a warning for the future. As we can see from our present social and political climate, the cautionary tale is still frighteningly relevant.

To check out a copy of the Handmaid's Tale from our catalog, click this link.

For more of Brian's book reviews, visit our Goodreads group.